Interview with Uli Decker (ANIMA) on production and working conditions in film

"Artistic documentary films also require openness to results to a certain extent"

A conversation with the director of the film ANIMA – DIE KLEIDER MEINES VATERS, Uli Decker, on the production and working conditions for documentary films.

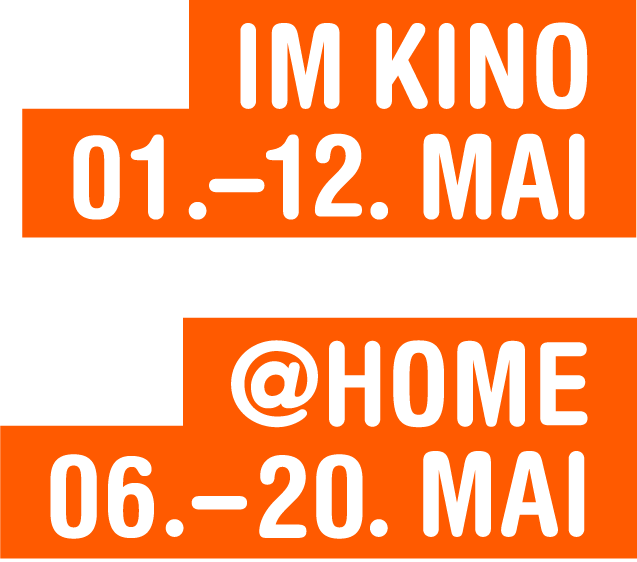

The Bavarian Film Award (Bayerischer Filmpreis) in the documentary category was presented in mid-June at the Prinzregententheater in Munich to Uli Decker for her film ANIMA – DIE KLEIDER MEINES VATERS – congratulations! The film screened at the 37th DOK.fest München in the Munich Premieres series in 2022.

Our festival director Daniel Sponsel (active on the board of AG DOK) spoke with filmmaker from Murnau, who lives in Berlin, after the award ceremony about the precarious production and working conditions for documentary filmmakers in Germany.

Daniel Sponsel (D.S.): Once again, congratulations on winning the Bayerische Filmpreis (Bavarian Film Award)! At the end of your thank-you speech on stage, you took the opportunity to address two important points: Firstly, your astonishment that your very personal film about essential questions of gender identity is so highly regarded in Bavaria. At the end you mentioned the difficult production and working conditions for documentary films and demanded that as a filmmaker you should receive a regular salary for a film.

Uli Decker (U.D.): Thank you very much! Yes, the positive response and the great interest in ANIMA is really gratifying. The fact that so many different people feel addressed by the film shows me that my team and I have succeeded in doing something really special.

Besides its queer themes in the broadest sense, ANIMA is above all a film about family dynamics, social taboos and the effect of secrets on our human connections. It was important to me not to make a niche film, but a film that could potentially appeal to a broad audience, including people who otherwise have little contact with documentary film. The fact that it was important to find a formally captivating, entertaining form and a tone that allows for lightness and humour in the midst of all tragedy was the great challenge in the making of the film. The long time it took to make the film (6 years) is due on the one hand to the fact that it meant a great effort for me to break through taboos that had accompanied me since my childhood and youth, and on the other hand to the very diverse form, which includes archive material, animation, documentary and fictional material. The tone of the film also required an intensive, precise working process in close collaboration with my team. Delays due to an accident in the production process and Corona did the rest.

What weighed heavily on me during the entire production process was that my work on the project went far beyond my contractually agreed duties as writer and director, and I had to make up for missing budget items at every turn with my own unpaid work, from additional camera work, securing archive material, the preparation of the shoot etc. to the professional editing of the foto material in the film – apparently that is a matter of course in documentary film and certainly not an isolated case. At the same time, I hardly knew how I was supposed to make a living from the meagre director's and writer's fees during the intensive production period.

D.S.: You could say that documentary film is at the bottom of the food chain in the economy of culture. Why is that, how do you experience it?

U.D.: My impression is that documentary film is not seen as a fully-fledged film in Germany – neither by large parts of a potential audience, nor by funding agencies, TV stations or production companies. An expression of this is, for example, that documentary film went unmentioned in the reports on the Bavarian Film Awards in the mainstream media, while the awards for feature film as well as the corresponding trades were reported on in detail.

This general ignorance of documentary film is probably due, among other things, to the fact that television programming has been extremely reduced in terms of the diversity of cinematic forms over the last 30 years. The audience is not expected to be interested in documentary films. In the television programme, they are put in the slot after midnight, in the cinema in the afternoon – times that hardly attract any viewers anyway.

Thus, the broader audience is rarely given the opportunity to see artistically demanding films. Any diversity is being levelled out with the argument of ratings – which should not play such a big role at least in the public broadcasters. More demanding formats would not generate ratings, so the argument goes.

Now, one could say: Today, television no longer plays a major role anyway. But Netflix and other popular streaming services also produce heavily formatted documentary forms. The variety of means of expression that are possible in film and especially in documentary film can only be seen there in isolated cases. Strongly formatted films are, after all, quicker and cheaper to produce and lead to predictable results.

Artistic documentary films also require openness to results to a certain extent. And that involves risks and is less controllable. A film like ANIMA, for example, needs time to mature and find its form. This is costly for all involved – and especially for the director and the production. The added value is multi-layered works that can touch people deeply, surprise with originality and inspire complex reflection on our society and the Conditio Humana.

D.S.: We have all been working on the issue of the economic conditions for producing documentary films for a long time and again. Thanks to the persistent negotiations of BVR (Bundesverband Regie, Federal Association of Directors) and AG DOK, there has been a remuneration arrangement for book and director fees with ARD since 2021. Now the amendment of the Filmförderungsgesetzes (Film Subsidies Act) is pending. What could be anchored in the law to make the production conditions for documentary filmmakers fair?

U.D.: The workload of the director should also be reflected in the fee. This means that all additional work that is not covered by the book and director's contract and that has to be taken on by the director should also be paid according to the usual scale of fees. If archive material owned by the director is brought in, royalties should be paid for it.

Editing times should be calculated realistically for the respective project from the outset – including the presence of the director in the editing room, which is often indispensable. Since the director's work is not over once the film is finished, but the director's presence at film screenings, premieres and festivals plays a major role in the distribution of the film, the distribution funding should also include an item for the director that compensates for the loss of working days with appropriate fees.

I consider a staggering of funding to be fundamental for realistic funding that fits the specific process of making a documentary film. Research and script development, book, production and post-production could be applied for in stages. The possibility should remain open to increase the total budget in the course of the process if it turns out that items were calculated too low at an earlier stage – which is often the case, but usually cannot be corrected once the total funding has been approved.

Paradoxically, this is common practice in extremely expensive, tax-funded construction projects such as the Elbe Philharmonic Hall or Berlin Airport. There, it is even accepted that the construction costs increase many times over from the initial planning to completion. In documentary film, on the other hand, there is no possibility to apply for even one cent more once the budget is closed.

A staggering of funding would have another major advantage: not every initial idea leads to a documentary film that needs to be published. Sometimes it only turns out later that a plan doesn't work out, protagonists drop out or are suddenly not available, reality has a different plan and it makes little sense to push a project. With gradual funding, projects would not have to be pushed through just because the funding has already been approved.

D.S.: In the context of the Berlinale, the 'Fair Film Award' is presented annually for fictional films. Crew United has also awarded this prize for non-fictional films in 2018 and 2019 as part of DOK.fest München. Is this a way to make the topic visible?

U.D.: It is certainly a step in the right direction. As directors, we are very vulnerable and dependent on the production companies with our often very personal themes, on which we often work for years with great personal commitment.

A 'Fair Film Award' would give directors important clues in their search for the right company, where we are in good hands with our project on different levels. It would not only be about the technical qualities of the respective company, but also about the human interaction with all those involved: Who treats us fairly and treats our work with respect? Are filmmakers involved in shaping the budget? Is there transparent, fair communication with the director? Are contract and fee negotiations respectful or do they try to exploit ignorance for the benefit of the production? Does a company continue to work for the distribution of the film after completion or does it leave the work to the director?

These and other questions are important points when deciding on a collaboration. It is extremely important for filmmakers to exchange views on this, because the choice of production company has a great influence on the working process.

D.S.: Thank you for the interview and the concrete suggestions and proposals. On the part of AG DOK, we are actively influencing the design of the Film Funding Act and can be optimistic that some of the points you mentioned will be taken into account.